Subscribe to continue reading

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

In spite of much grey and much rain (I miss snow!), December has been a happy month. This is because of several great concerts and events and connections with my dear ones near and far. And Christmas of course.

And besides all that, I’ve had cataract surgery: the right eye at the end of November, and the left just four days ago. What a gift! The world is freshly crisp and bright! By now I know quite a few people who have had cataract surgery, which people my age often eventually need, but I knew very little about it until I was informed that I had growing cataracts and that I might want to consider surgery. As it turned out, it’s not painful (the colours I saw and the water swooshing during the brief procedure was even pleasurable). And, it makes a difference. That’s the point of it, right? During the weeks when only the right had been done, I often closed one eye and then the other to make the comparison. Yup, sky still grey but in the “new” eye a bright grey and in the un-done eye, yellowish grey. It reminded me of the effect of the purple shampoo I use occasionally to mute the brass and enhance the silver in my hair.

For a day or so after the surgery, the pupil as big as a dinner plate compared to the other, lights had radiant spokes and a ring of light around them. Thus my Christmas tree four days ago was covered in overlapping wheels of light. I thought I should take a picture of it, until it occurred to me that the camera lens would not pick it up, it was my lens that was doing this.

Also some books

I’ve also been able to read quite a bit this month. I enjoyed Trinity by Leon Uris, about Ireland; Children Like Us by Brittany Penner, a Métis-Mennonite memoir; The Mind Mappers, about Wilder Penfield and William Cone of the Montreal Neurological Institute; The Land in Winter by Andrew Miller, on this year’s Booker shortlist.

Currently I’m reading Book of Lives by Margaret Atwood. My granddaughter Maia treated me to an Atwood appearance at the Vancouver Orpheum, which was lovely, especially on account of Maia’s company, and now my library hold of the book arrived. I confess that I was dismayed to see it’s massive — 570 pages, not including the index. There’s been quite a few longish books lately already. (Any good short books to recommend?) And this one is detailed; I’m up to page 90 and she’s barely in high school. I find happy childhoods rather boring, actually, though there was the year she was 9, in which she was tormented by the leader of the girls’ foursome she was in, which she used as grist for her novel Cat’s Eye. I remember reading that book, how powerful it was, and even though I didn’t have a mean-girl Cordelia in my growing-up years, I can clearly recall an instance of the Cordelia-like Barbara mimicking me. I’ve forgotten almost everything from my junior high years, but I have not forgotten the feeling of that moment. Yes, we probably all know Cordelias.

Also interesting, when several years later the tables had turned and Atwood was now the more powerful one in relationship with this “friend”, she got her comeuppance, and in my opinion it was rather mean too. Mild, she calls it, but mean is as mean does. — I’ll definitely read on, and I know how to skim if need be. I do want to get out of her childhood and youth and into the writing parts.

Thank you all for joining me here at Borrowing Bones this year. I wish you a safe and joyous 2026!

On Sunday, a bird crashed into a window at my son’s house. I was in the room, relaxing, as was my daughter-in-law and a granddaughter. We heard the impact, saw feather stain on the glass, jumped up to see what had happened.

“What if it’s Grandpa?” the granddaughter burst out.

This startled me, though our more immediate concern was the fate of the bird, which now lay some distance from the window. (As it turned out, sadly it was dead.)

I’ve been thinking about the girl’s remark, made in that moment when we could still simply imagine the bird wanted, as it were, to join us. She knows how much her grandpa — my late husband Helmut — loved birds.

In Winnipeg, his favourites were robins. To him, a robin building a nest in one’s yard was a bestowed blessing. I remember how thrilled we were by the delicate blue-green eggs in their nest, and how devastated when we found the nest emptied not long after, by some predator we assumed, and the parents gone too.

Here in Tsawwassen, B.C. it was eagles he loved, for they are numerous during winter months, and also hummingbirds, which he could watch year round at a feeder on our bedroom balcony. One day, about six weeks before he died, at a point when pain had once again intensified to a new level and the pain medication dosage once again inadequate, he was weepy. He went through four or five Kleenex tissues and I was crying too. We were both weary. He told me an eagle had swooped low by the window and there had been a hummingbird at the feeder. He would like, he said, to be “between”. I didn’t ask what he meant by this because I think I knew.

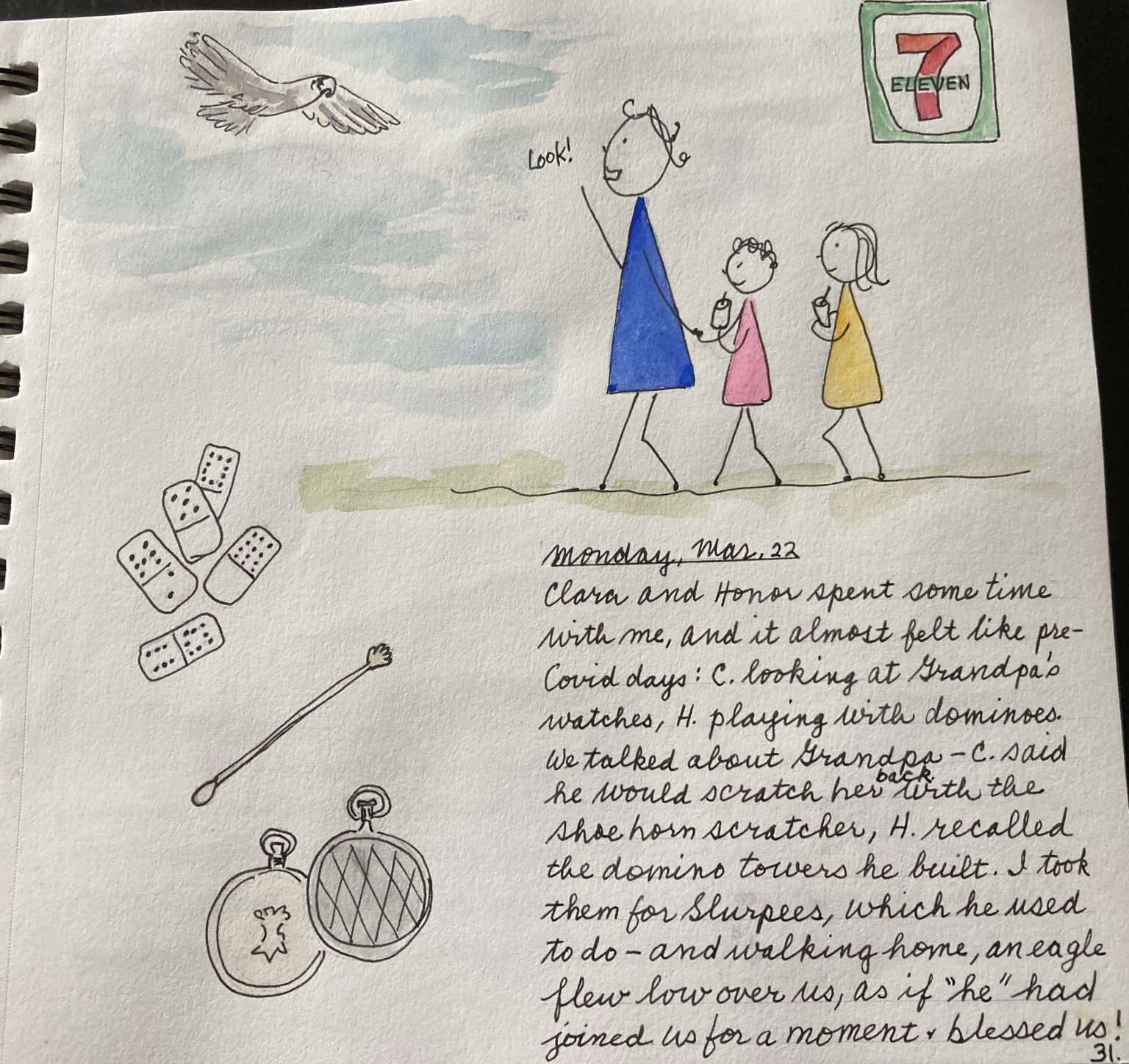

In many cultures and spiritual traditions, birds have long been considered links, even messengers, between Earth and Beyond. (Perhaps because they have wings?) At the very least, they’re symbols — the eagle of strength, for example, the hummingbird of joy. There’s a saying, “When robins appear, loved ones are near.” I’m not dogmatic about such meanings, coincidence is perfectly fine for me, and I’m content in the mystery as well as my granddaughter’s response. But, while not a birdwatcher per se, I’ve had encounters with birds that not only reminded me of Helmut but brought profound consolation which seemed intended for me. I usually keep these moments for myself, for there’s vulnerability in them, but here is one instance I documented in a grief journal of words and little stick-people drawings I kept the first months after his death, which I hope makes you happy too!