Besides resolving to appear here monthly in 2025, I had a second New Year’s resolution: to read Moby-Dick. Which I have just accomplished, thus plugging one of many holes in my education. It wasn’t exactly a page-turner (not to mention there are a lot of pages to turn) so I read it alongside other books, aiming for two chapters a day. But I enjoyed it. I learned a great deal about whales and whaling, and was carried along by Captain Ahab’s mad quest for the White Whale and by Ishmael’s erudite and often humourous voice. About the latter, Alfred Kazin says:

But the most remarkable feat of language in the book is Melville’s ability to make us see that man [sic] is not a blank slate passively open to events, but a mind that constantly seeks meaning in everything it encounters.

Speaking of meaning, I commend to you a link that young friend Chris Friesen included in a comment to last month’s post, in which I talked about the present “moment.” It’s a sermon he preached at the church we attended in Winnipeg. He weaves together his love of bugs, coming to the edge of meaning, and the strange scriptural book of Ecclesiastes. His conclusion has stuck with me: “the moment becomes the site of meaning.” It’s worth a read.

I think I mentioned some time ago that I have a new book of short fiction coming up, for publication next spring, with Freehand Books. I’m in the edits stage now, and have just gone through the manuscript again and sent it back to my editor. With that task done, I was able to welcome, with an unfettered schedule, my daughter and her wife and two children, who returned to B.C. from their new digs in Nova Scotia this week to celebrate their wedding, which actually took place five years ago but during Covid and thus minus the intended public celebration. All my children and grandchildren will be together for that, and we’re looking forward to it.

And, this month, two additional books to mention. I’m not Catholic, but I admire Pope Francis and I’m enjoying Hope, his recent autobiography. There’s a warm lively aspect to his recollections, also honesty about “errors and sins,” as well as an embrace of sentiment as “a cherished value: not to be afraid of feeling.” I remember following the election of a new pope in 2013, after Benedict’s resignation, scanning the various possibilities and so on. I checked back in my journal to see what I’d recorded (and see that I wrote in the second person, as I do now and then):

…you feel you should see where matters stand with the Vatican conclave. Well. The white smoke has billowed forth, not 10 minutes ago. So you join Peter Mansbridge (CBC) to watch live, and who is it? The one you hoped for from that list of 20 [in the newspaper], the man from Argentina, and on what basis did you hope? Well none are anything but traditional but there was a note, wasn’t there, of openness to women? On that basis. He is a Jesuit, of pastoral personality and warmth, simple habits, etc. What you’re reading seems affirming. It’s a surprise, of course; he was not in the upper group of likelies. He’s 76. Latin Americans are thrilled.

Actually, women’s position in Catholicism has not changed much, as far as I know, but I’m only about a third in so perhaps he will comment on it further in. (Here’s the Guardian review.) Another book I’m reading is the graphic edition of Timothy Snyder’s On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons From the Twentieth Century. The illustrations by Nora Krug add power to Snyder’s 20 points; the whole thing is just incredibly relevant.

Actually, women’s position in Catholicism has not changed much, as far as I know, but I’m only about a third in so perhaps he will comment on it further in. (Here’s the Guardian review.) Another book I’m reading is the graphic edition of Timothy Snyder’s On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons From the Twentieth Century. The illustrations by Nora Krug add power to Snyder’s 20 points; the whole thing is just incredibly relevant.

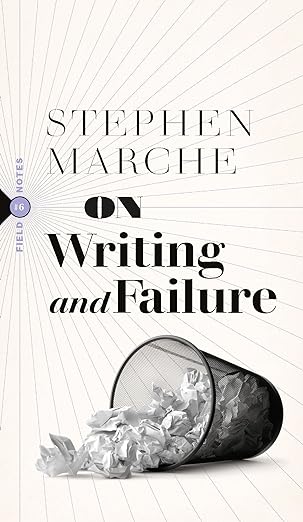

but to keep at it, to keep submitting the work. “No whining,” he insists repeatedly. “The desire to make meaning…is a valid desire despite the inevitability of defeat.”

but to keep at it, to keep submitting the work. “No whining,” he insists repeatedly. “The desire to make meaning…is a valid desire despite the inevitability of defeat.”