This week I attended, with my sister and brother-in-law, an exhibit at the Mennonite Heritage Museum, Abbotsford, B.C., called “Unearthing the Vanished: Mennonite Experiences in Stalin’s Great Terror.”

It tells the stories of some of an estimated 9000 Mennonites — generally men — arrested during the Terror of 1937-38 in the Soviet Union. These stories are but a sampling of the 9000, and the 9000 itself but a portion of the number in the larger population who were affected in that period. (See, for example, books like Solzenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago.)

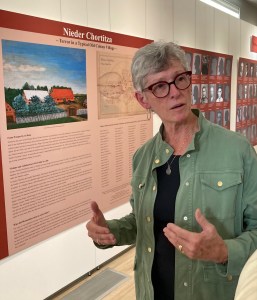

Janet Boldt, one of the writers/researchers of the exhibit, whose own relatives were taken in the Terror, gave us an excellent introduction to the exhibit.

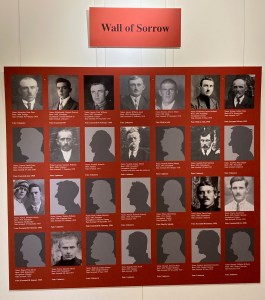

In panels of text, photos, art, and poetry, and materials like a boy’s begging cloth and copies of trial documents, the exhibit presents the background to the Terror, details of arrests and interrogation and sometimes (if known) outcome, as well as faces in a 3-panel Wall of Sorrow. Even starker than photos are simply names with “profile cutouts.” In many cases, all that can be said is “Fate unknown.”

“Take a moment to gaze at their faces,” the exhibit guide advises. “[A]ll were part of the fabric of society, all were part of what it means to be family.”

A wail of lament

The exhibit also addresses the affect of these arrests and disappearances on women and on children. Collectively, it’s emotional; it’s moving. It’s a wail of lament.

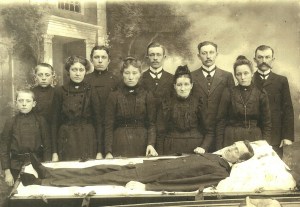

I can’t help thinking of a 1912 funeral photo (below) of my grandfather’s family (he’s the second from right in the back), at the time of his father’s death. Of these siblings, only he and one brother, far left, would later manage to immigrate to Canada. What was the fate of the rest of them? A few letters in the early 1930s speak of Verbannung (exile) and great hunger. Of her family, my grandmother wrote, “If only I knew where all our family members are…. What happened to them all?”

Of her family, my grandmother wrote, “If only I knew where all our family members are…. What happened to them all?”

It’s also impossible to look at this exhibit and not think of images and videos we see in the news every day, not arrests into a “Black Raven” vehicle at midnight but masked and often unidentified ICE agents seizing people in broad daylight. Reports of terrible treatment in places like Alligator Alcatraz are emerging. There seems no recourse in these grabs to lawful procedures or justice. It’s neither alarmist nor conspiracy theory to draw parallels between the “disappeared” of my heritage and today’s new masses of the “disappeared.”