I don’t know when I’ve seen a single category of my internet homepage, Arts & Letters Daily, here, as full as now with its collection of articles reflecting on the fall of the Berlin Wall, 20 years ago on Monday. 1989, it announces, was the biggest year in world history since 1945.

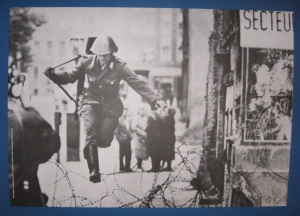

Twenty years is not so long. Even the relatively young among us will surely remember it. Two of our kids brought home the famous Checkpoint Charlie poster — of the young soldier jumping to freedom — from their student exchange trips to Germany. We drymounted them and the image of freedom’s leap hung in their rooms until they left, a memory, perhaps, of their first short travels away. One of the posters got taken along, the other lies in the childless room, turned store room of sorts, the poster slightly warped but now also a memory of our children’s presence in our house, and the way they decorated their space.

I remember the fall of the Wall, of course, but looking back in my journals of Nov. 1989, I don’t find a word written about it. My only excuse is that I was in some excitement and tremor of my own, as my first book had just been released.Still, you’d think I could have mentioned the Wall. It’s the nature of personal journalling, I suppose. I do know we were all rather taken with Mikhail Gorbachev.

Of a day nearly a year later, Oct. 3, 1990, however, I have notes. I was sitting in the public library, Henderson Branch, overwhelmed by the official re-unification of the two Germanys that day, and jotting lines trying to make sense of why it mattered to me, why I was so happy.

I wasn’t alive in 1945 when the Enemy was humbled to just proportions… when corpses formed Babels of perversity… when photographs were made of naked men / hands clutched to cover circumcised shame in the moment just before they died… In books and television and history lessons of all kinds, I had had images and words to educate my shock, determined I would look but never comprehend it …

Remembering the awfulness, the evil of it, how, as quotes from Nazism, A History in Documents and Eyewitness Accounts, 1919-45, Vol. 1, remember it, how Germans called the Fuehrer “Lord,” their “creator and preserver, the protector.” They actually said, “every flower… blooms in gratitude to him…” Quotes about Kristallnacht, and laws about everything that was newly forbidden: Jewish, that is. Surely they were pagans…

Far from that time and place, I grew up with Gentle Jesus and the children, his kind and undivided face… And in my youth, reading A.M. Klein, echoing his wrath, his double deuteronomies…

Here’s the thing. My very first language was German. [But I assure you it means nothing.] By school time, though, it was only English that we spoke. My mother had no qualms to sing, “There’s Always Be An England.” I kept a scrapbook of the royal family. I’d grown up thoroughly Canadian, absorbed the British-centric country of my childhood.

Hadn’t I?

So why, in light of my hatred of, in light of my resistance to this Germany and what they’d done and the division they’d surely deserved, why the tears of happiness, watching jagged lumpen shapes of West and East, separated twins of history, re-form… the atlases of unredeemed history redundant at midnight…

Was it a kind of forgiveness then? Two now one, when a thousand pieces scattered would not have been too many?

I insist it was an accident, that I heard my first truth in their language… Gott ist die Liebe [God is love], and over and over the crucifixion story, in German, until my mouth was splintered… gagging on Seven Last Words

until the Eighth:

Congratulations!

It still seems complicated. Country and language and what they mean. And also champagne… sparkling everywhere / inside me / over vestiges of walls / across the burial pits of slaughtered Jews.